When I was growing up in Kent in the 1980s, my mum would make sure I had a window open each night before I went to sleep. If the window was open before all the lights were turned off, there would be an invasion of moths and flying insects, whirring around the room. Through the 1990s they dwindled, and by 2000, on visits home, it didn’t really matter whether I opened a window with a light on. The insects had vanished.

I told a Colombian friend about this in the early 2000s, and he responded with his story. Something similar had been happening on the other side of the world. But only in 2017 did the vanishing of insect populations hit the headlines in the UK. Why is it taking us so long to pay attention?

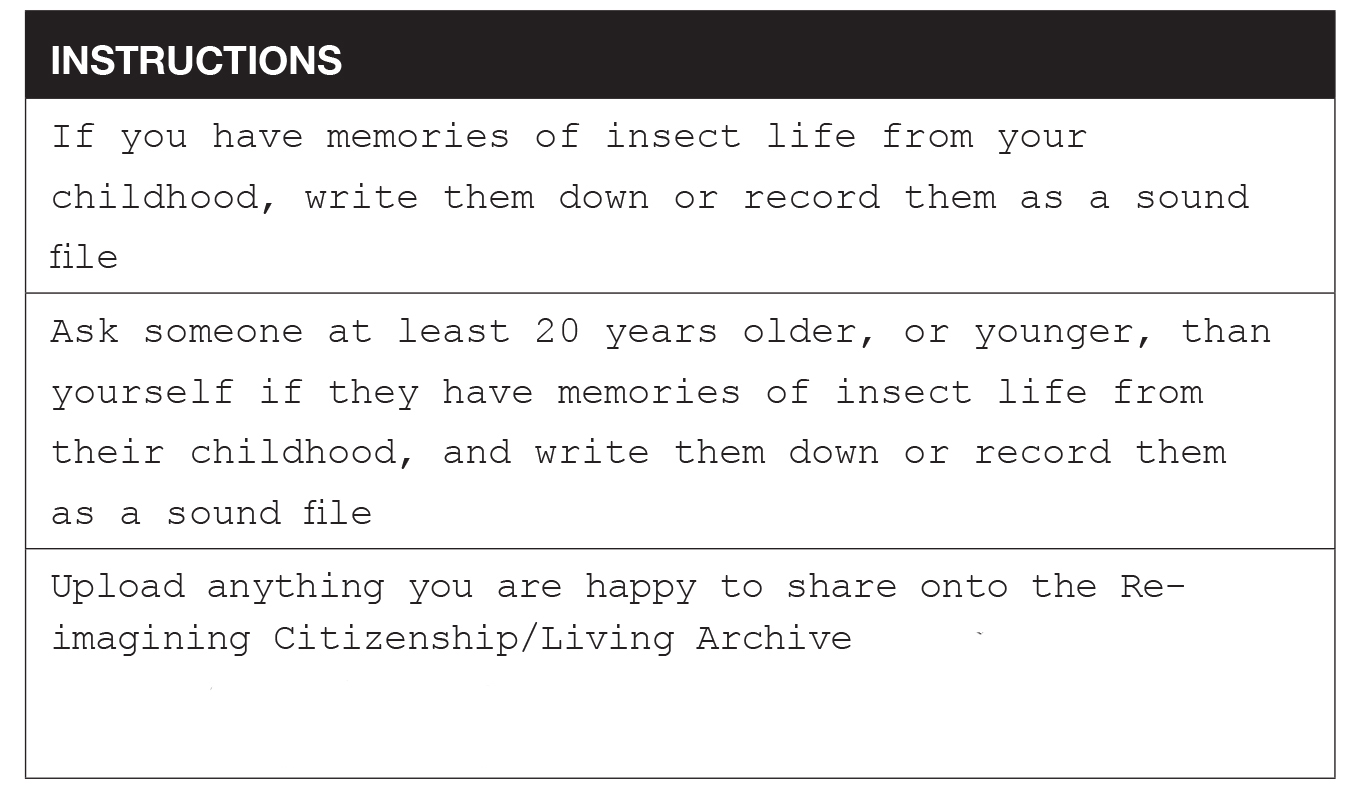

Some of the worst crises facing humans and other species cross national borders. What kinds of reimagining do our times call for?

INSECTOS VOLADORES

Recuerdo de mi infancia aquellas vacaciones en la finca cafetera de nuestros padres, en el municipio de Manizales, Colombia. En el día jugábamos entre los cultivos de café, yuca, plátano, frutas y las zonas boscosas. Llegábamos a casa cansados y picados nuestros cuerpos por hormigas y diferentes tipos de mosquitos que cambiaban el dolor de su picadura según la temporada del año. Nada de esto impedía nuestra felicidad por explorar la montaña. En horas de oscuridad las historias que contaba nuestro padre nos hacían ver seres vivientes entre las sombras que producían las velas y los dos bombillos que poseía la finca. Gastábamos horas observando los miles de mariposas, polillas, cucarrones, grillos, mosquitos, zancudos que se aglomeraban alrededor de los focos eléctricos, y jugábamos a quien encontraba el insecto más extraño y si este se parecía a una nave espacial, un carro o un avión. Cuarenta años después conservamos la finca con sus bosques intactos. Aun es rica en flora, pájaros y reptiles, pero siento nostalgia en la noche cuando alrededor de las bombillas ya no nos visitan esos ejércitos de insectos infinitos en sus formas y colores. Aun así y con los pocos que quedan, sigo buscando en ellos las naves espaciales como si quisiera de nuevo viajar por los mundos imaginarios de mi infancia.

FLYING INSECTS

I remember childhood holidays spent on our parents’ coffee farm in the municipality of Manizales, Colombia. During the day we would play among the plantations of coffee, cassava, plantain and fruit and in the wooded areas. We would arrive home tired, our bodies covered with bites from ants and different types of fly, which varied in how painful they were, according to the season. None of that spoilt our happiness exploring the mountainside. When it was dark our father told stories that made us see living creatures in the shadows cast by the candles, and the two electric bulbs in the farmhouse. We would spend hours observing the thousands of butterflies, moths, beetles, crickets, flies and mosquitos that congregated around the light, playing at who could find the strangest insect and whether it looked like a space ship, car or plane. Forty years later we still have the farm, the woods still intact. The farm is still rich in flora, birds and reptiles, but at night I feel nostalgia when we, and the lightbulbs, are no longer visited by those armies of insects and their infinite forms and colours. Even so, among the few that remain, I still look for space ships, as if I might travel again through the imaginary worlds of my childhood.

Symbiotic citizen Petersen

Zoë Petersen is an artist and PhD researcher with the School of the Arts at Loughborough University. Roberto Ceballos, who contributed the story from Colombia, is a music teacher trained at the Universidad del Cauca, Middlesex University and the London Institute of Education. He is also a small-scale coffee farmer.